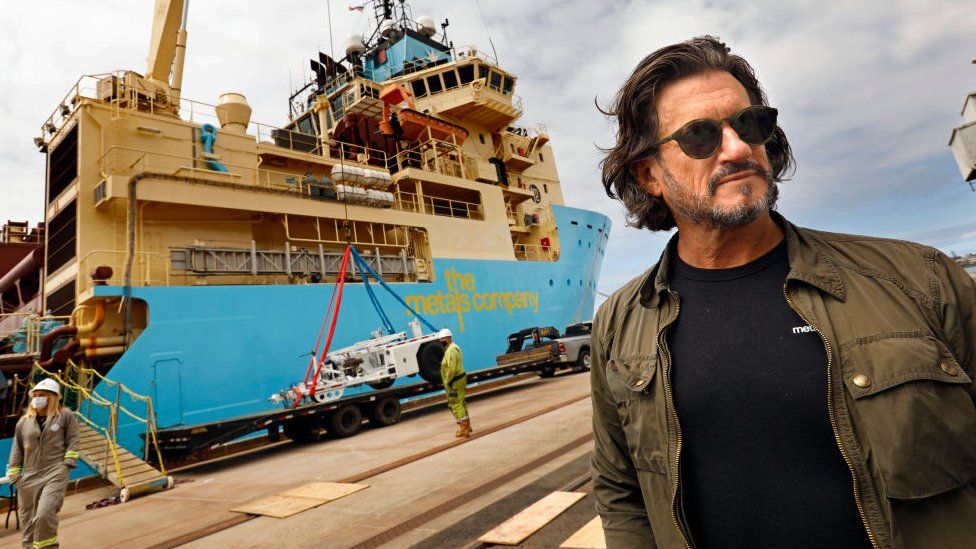

Deep-sea miner Gerard Barron insists that his company's extraction method has little impact on the environment.

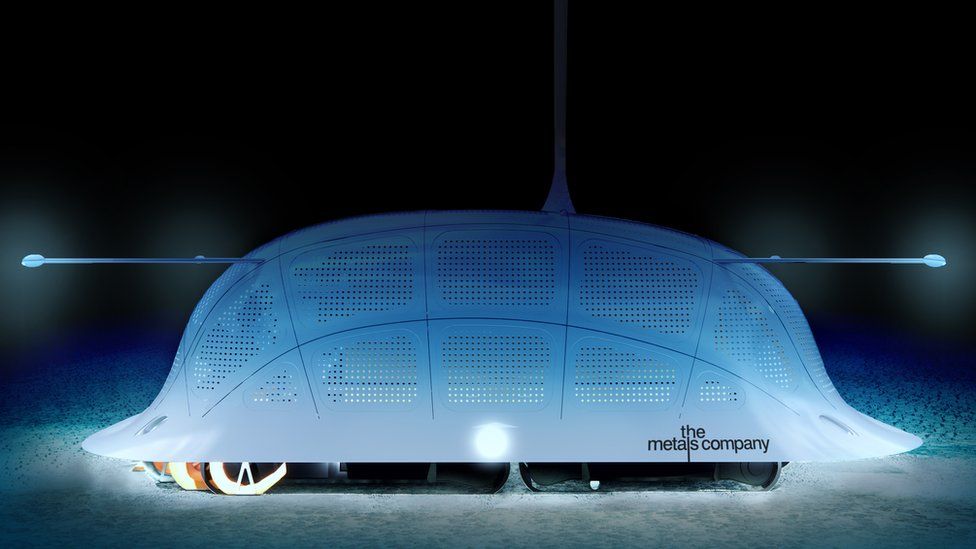

His firm, The Metals Company, uses remote-controlled machines the size of trucks "to scoop up rocks sitting on the sea floor".

These rocks are then crushed and processed to release a number of key minerals in high demand for the production of batteries - cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese.

Currently continuing testing work, the Canadian business hopes to get authorisation to start commercial mining in international waters in the north Pacific as early as the end of 2025.

At present such commercial extraction is not allowed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the UN body that regulates the seafloor in international waters. However, the ISA and its 169 member states, are due to meet later this year to try to finalise rules that may potentially allow it to start, with a final vote expected within 24 months.

Some 30 countries including the UK, Brazil, Canada, France and Germany want the ban tocontinue because of concerns about the environmental impact. However, other nations, including China, are keen for large-scale deep-sea mining in international waters to get the go-ahead.

It comes as Norway made headlines last week when it became the first country in the world to allow future deep-sea mining in its territorial waters. The US is exploring the possibility of doing the same, with President Biden ordering the Pentagon to submit a report on the issue by 1 March.

This move follows after 31 members of Congress wrote an open letter about deep-sea mining in December, saying that the US "must explore every avenue to strengthen our rare earth and critical minerals supply chains".

In addition to harvesting rocks (more formally called "polymetallic nodules") lying on the seabed, other deep-sea mining methods are more invasive, and involve digging down.

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is opposed to all deep-sea mining on the grounds that it says it presents an unacceptable risk to marine life.

"If the industry proceeds, the intensity and methods of deep seabed mining could destroy entire habitats and species," says Kaja Loenne Fjaertoft, a marine biologist and senior advisor for sustainable oceans at the WWF.

"Many species living in the deep sea are found nowhere else. Disturbances in just one mining site could wipe out entire species."

She adds: "As well as the direct destruction of ecosystems when minerals are mined, major damage and disturbance would likely arise from light noise and sediment pollution."

This concern is echoed by the European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC), the independent body that guides the EU on its scientific policy. "It's unavoidable that the actual process of mining is physically disruptive, and would more or less wipe out any biota [animals and plants] in the areas directly mined," says the EASAC's environment director Prof Michael Norton.

"There's also a chance of second-level effects on the adjoining sea beds or adjoining water column."

Prof Norton also questions the need for deep-sea mining in the first place. "It produces a lot of manganese, which we're not short of. It produces, in some cases, cobalt and nickel, which are actually used in some of the clean energies, for instance, batteries, but they're not rated by the European Commission as being particularly at supply risk."

The area of the north Pacific that The Metals Company wants to mine is called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. This is a vast section of ocean located between Hawaii and Mexico, which measures 4.5 million sq km (1.7 million sq miles).

Mr Barron says that mining here would cause far less environmental disturbance than existing mining on land. He points to current nickel extraction, where the world's largest two producers are Indonesia and the Philippines.

There has long been concerns about the impact this mining has on rainforests in both countries.

"The area we're focused on, where these rocks sit, is the abyssal zone," says Mr Barron. This perpetually dark zone is 3,000m to 6,000m (10,000ft to 21,000ft) below sea level.

"Here there's zero flora. And if we measure the amount of fauna [animal life], in the form of biomass, there is around 10g per square metre. That compares with more than 30kg of biomass where the world is pushing more nickel extraction, which is our equatorial rainforests."

0 Comments